Author(s)

Emerging economies are not just the next frontier of clean energy investment; they are the stress test for the global financial system’s ability to value the future. Over the next decade, over 70% of global energy demand growth will occur outside the OECD, yet these same regions attract less than 15% of global clean energy capital. The arithmetic is staggering: an annual USD 1.3 trillion financing gap separates current trajectories from what’s needed to align with 1.5°C.

This is not a story about money; it’s about risk perception, institutional design, and epistemic credibility. The real challenge is not mobilizing capital but redefining how the financial system prices transition risk in economies where policy, currency, and political volatility obscure otherwise bankable opportunity.

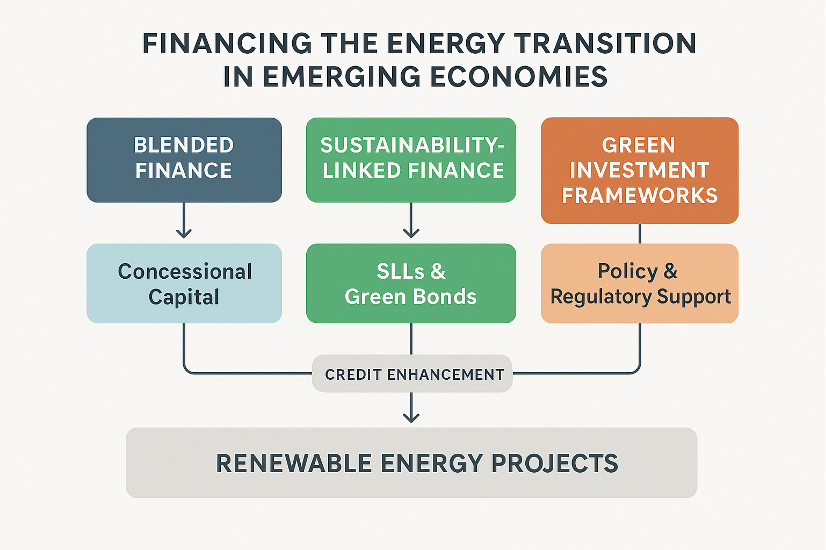

Blended Finance Must Evolve

The discourse around “de-risking” in emerging markets often assumes that risk is exogenous, something to be mitigated rather than reinterpreted. Yet, in truth, transition risk is endogenous: it arises from the design of capital instruments that fail to internalize the value of decarbonization.

Blended finance, as currently structured, remains palliative. According to IEEFA, each dollar of concessional capital mobilizes roughly USD 5–7 of private investment, but these ratios flatten without structural reforms to local capital markets and policy durability. Blended finance derisks projects but not systems; it lowers the cost of capital without building endogenous confidence.

Consider the Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) in Southeast Asia: by securitizing stranded coal assets and channeling proceeds into renewables, it creates fiscal breathing space, but it also embeds a moral hazard if carbon-heavy balance sheets are socialized without robust closure frameworks. As Nature Energy warns, mechanisms that compensate incumbents can become carbon bailouts if not paired with stringent phaseout clauses. The next generation of blended finance must move from “de-risking” to “re-pricing,” embedding climate transition into sovereign creditworthiness, integrating carbon-adjusted discount rates, and valuing social stability as a financial asset.

Sustainability-Linked Finance

Sustainability-linked loans (SLLs) and bonds were meant to democratize ESG finance, tying cost of capital to environmental outcomes. Yet, by 2024, global SLL issuance exceeded USD 1.5 trillion, and a significant share carried weak or self-reported KPIs. The paradox is that cheap capital without accountability breeds fragility. Nearly 40% of SLLs lacked third-party verification of emissions reductions. This credibility gap is existential; if the market loses faith in ESG metrics, the cost of capital for sustainable assets will spike, punishing the very actors driving transition.

Emerging economies can lead here. Unlike legacy markets bound by disclosure inertia, new frameworks in Chile, South Africa, and India are piloting digital MRV systems, using satellite data and blockchain registries to verify renewable generation and social co-benefits in real time. If scaled, such a credibility infrastructure could cut transaction costs and strengthen investor confidence, doing more for bankability than any concessional fund. The provocation is this: sustainability finance must be auditable to be investable. In an era where data is more valuable than guarantees, transparency itself becomes the ultimate collateral.

Green Investment Framework

The most radical insight emerging from the various frameworks is that financing the transition is not about redistributing capital, but redesigning risk perception. The old model where concessional finance “crowds in” private investment is giving way to a networked capital architecture, in which sovereign wealth funds, multilateral banks, and institutional investors co-invest on equal footing under shared ESG frameworks.

This is already visible in Kenya’s Green Energy Facility, which mobilized domestic pension funds alongside concessional financing, effectively localizing ownership of the transition. Such structures internalize resilience returns accrue domestically, currency risks are shared, and capital cycles stay within the region.

Yet the missing link remains sovereign credibility. The IEA estimates that improving credit ratings by one notch could reduce clean energy borrowing costs by 30–40% in Africa and Southeast Asia. Thus, macro-financial reforms, carbon pricing, fiscal transparency, and policy predictability may have a greater impact than any single technology subsidy. Ultimately, the goal is not merely to finance the transition but to institutionalize climate credibility to make decarbonization bankable without dependence on Northern capital or concessional buffers.

Conclusion

The financing of the energy transition in emerging economies is not just an investment story; it is the reconstruction of global economic logic. Sustainability must be treated as a risk reduction mechanism, not a reputational luxury. Investors who understand that carbon volatility is financial volatility will find asymmetric opportunity in markets long dismissed as risky.

The path forward demands not more money, but smarter money, capital that prices resilience, transparency, and sovereignty as value drivers. The countries that master this synthesis, credible policy, digital verification, blended design, and local co-ownership, will not only leapfrog to clean energy, but redefine the political economy of global finance. When the financial system learns to price time as an asset, not a liability, the energy transition in emerging economies will finally become investable, equitable, and unstoppable.

Analytical Framework